By David Carr, Director, Blandy Experimental Farm

The history of Blandy Experimental Farm is intertwined with an older, crueler history. The property was once a part of what came to be known as the Tuleyries, dating back to Joseph Tuley Sr. in the early 1800s and later Joseph Tuley Jr., his son. In about 1830, it was Joseph Tuley Jr. who commissioned the Tuleyries mansion that stands just west of Blandy. The Tuley family enslaved dozens of people who labored on this land and in their household into the 1860s. The Tuleyries passed through other owners in the time between the end of the Civil War and Graham Blandy’s donation of 700 acres of the estate to the University of Virginia, but we are still trying to reckon with its antebellum history here in the 21st century.

The most obvious reminder of the property’s legacy of slavery is the east wing of the Quarters building, which served as a barracks for many of the enslaved laborers of the Tuleyries. Another part of that legacy has remained hidden from view – an unmarked cemetery located within the Arboretum. We know of the existence of the cemetery from a plat copied in 1925 from a 1904 property survey, but its exact location remained a mystery until recently.

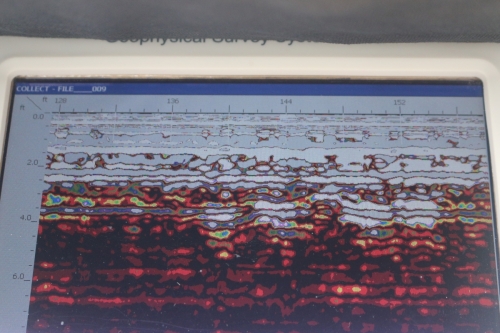

Ground-penetrating radar was used to detect graves based on anomalies in the soil structure.

Curator T’ai Roulston was able to use existing landmarks from the century-old plat to develop latitude and longitude coordinates to mark the likely corners of the cemetery. We then contracted with a Leesburg, VA company (GeoModel) to survey the site with ground-penetrating radar. The radar can detect anomalies in the soil structure to depths of about 15 feet. It turned out that T’ai’s translation of the old data was remarkably accurate.

GeoModel was able to detect evidence of 40 graves within the projected boundaries of the cemetery. Outside of those boundaries, the radar detected no soil anomalies, indicating that nobody had ever disturbed the soil to the depth of a typical grave. This gives us reasonable confidence that we were able to detect all of the graves.

With near certainty, given the data collected thus far, each of those 40 graves represents a person who lived and died in bondage, treated as property in life and intentionally left to be forgotten in death. The way that graves are grouped suggests that families perhaps were buried together. They were mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, but we do not know who any of them are. We may never know. But now, they are no longer completely invisible, nor is the shameful history that ties them to this property.

Four unmarked graves show up as soil anomolies in this ground-penetrating radar image.

The effort to find these graves is just one of several initiatives we are taking to bring the history of this property to light. We intend to mark the boundaries of the cemeteries and each grave within it. We also will be hiring an intern this summer to help us with archival research that we hope will teach us more about the lives of the enslaved laborers of the Tuleyries. Perhaps our research might someday enable us to identify living descendants and lead to the creation of an appropriate memorial. Our efforts will not provide justice for those who lived and died here, but we will strive to ensure that they are not forgotten.

We know that much of the history of slavery is scattered and hard to find. If you know about records or family stories linked to the history of slavery at the Tuleyries that you would like to share, we welcome you to contact us.

(This article originally appeared in the Spring, 2021 edition of Arbor Vitae, Blandy's newsletter. For more information about the history of Blandy Experimental Farm, visit https://blandy.virginia.edu/content/blandy-history. There is also video of a panel discussion about the history of enslavement in the Shenandoah Valley held at Blandy on November 11, 2022 on our Youtube page. and an article from The Winchester Star which details the efforts to find descendents of the enslaved at The Tuleyries.)